The Lessons of Theodore Roosevelt: How to Escape Our Second Gilded Age

In the college admissions scandal, one of the parents, a high-powered hedge fund lawyer, was caught on an FBI wiretap confiding, “To be honest, I'm not worried about the moral issue.”

Jeffrey Epstein’s alleged procurer of young female victims, Ghislaine Maxwell, herself the scion of a wealthy U.K. press magnate, reportedly told a friend, “They’re nothing, these girls. They are trash.”

After attorney Michael Cohen proposed paying an ex-Playboy model $150,000 to keep quiet about their affair, Trump replied, “Yes…get it done.” And when the risk of incriminating papers held by a tabloid owner might be leaked came up, Trump retorted, Corleone-like, “Yeah, I was thinking about that…Maybe he gets hit by a truck.”

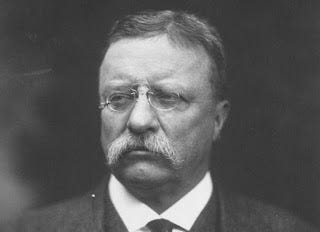

We now find ourselves in a Second Gilded Age, as in the first, marked by moral, political and financial corruption. If we don't get ourselves out of it, we risk decline as a society and a nation. Theodore Roosevelt can guide us out --

My latest article in Washington Monthly:

To get out of our Second Gilded Age, look no further than how we got out of the first one.

We’ve been rocked by scandals over the past year involving the nation’s most wealthy and powerful. We’ve learned that a twisted multimillionaire allegedly procured and raped girls in his Manhattan mansion and on his private Caribbean Island; entitled celebrities and corporate plutocrats paid millions of dollars in bribes to get their kids into elite universities; pillars of the Hollywood and media establishments have used their stature to sexually prey upon underlings; and, yes, our president was caught lying about possibly violating campaign finance laws with hush money payoffs to a porn star and Playboy bunny.

This moral corruption is accompanied by the regressive government policies of a scandal-stained administration. President Donald Trump is rolling back programs that protect consumers, voting rights, the environment, and competitive commerce faster than Congress can issue subpoenas. His cabinet includes 17 millionaires, two centimillionaires, and one billionaire with a combined worth of $3.2 billion, according to Forbes. He presides over the most corrupt administration in American history, one marked by nepotism and self-dealing. His so-called “A Team” of senior officials has undergone a record 75 percent turnover since he took office—most of whom resigned under pressure, often caught up in scandal.

Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, whose net worth is estimated at $600 million, reflected the arrogance and empathy deficit that typifies the Trump White House during last winter’s record-long government shutdown. He suggested that federal workers just take out loans until they got paid.

But nobody tops the swamp king, Trump himself. Forget the sleaze, forget the obstruction of justice, forget the constant dissing of Congress. His defying the Constitution’s emoluments clause alone would, in a normally functioning American democracy, make him the subject of impeachment. Instead, he flouts the rules as if they don’t apply to him. If he gets his way and hosts next year’s G-7 summit at Mar-a-Lago, we may as well send the Constitution to the shredder. And yet, as more recent controversies have shown us, including the Varsity Blues college admissions scandal and Jeffery Epstein’s sex trafficking racket, this kind of indifference to moral values is not confined to government grandees.

So, what gives? Is America drowning in a marsh of unchecked corruption and entitlement brought on by latter-day Louis XVI’s and Marie Antoinettes? Are the uber-wealthy out of control? There’s something rotten in America and, if we don’t fix it soon, we invite a new wave of national decline and social disintegration.

The good news is that we have faced similar challenges before. Some prescriptions from a previous era may provide a lodestar for a future Democratic president to steer the country in the right direction. As Mark Twain, who coined the term “the Gilded Age,” once said, “The external glitter of wealth conceals a corrupt political core that reflects the growing gap between the very few rich and the very many poor.” He was talking about the original Gilded Age, but that diagnosis could just as easily apply to our current American condition.

The first Gilded Age was marked by rapid economic growth, massive immigration, political corruption, and a high concentration of wealth in which the richest one percent owned 51 percent of property, while the bottom 44 percent had a mere one percent. The oligarchs at the top were popularly known as “robber barons.”

Theodore Roosevelt, who was president at the time, understood that economic inequality itself becomes a driver of a dysfunctional political system that benefits the wealthy but few others. As he once famously warned, “There can be no real political democracy unless there is something approaching economic democracy.”

His response to the inequities of his times, which came to define the Progressive Era, have much to teach us now about how to sensibly tackle economic inequality. It’s worthwhile to closely examine the Rooseveltian playbook. For instance, his “Square Deal” made bold changes in the American workplace, government regulation of industry, and consumer protection. These reforms included mandating safer conditions for miners and eliminating the spoils system in federal hiring; bringing forty-four antitrust suits against big business, resulting in the breakup of the largest railroad monopoly, and regulation of the nation’s largest oil company; and passing the Meat Inspection Act and Pure Food and Drug Act, which created the FDA. He prosecuted more than twice as many antitrust suits against monopolistic businesses than his three predecessors combined, curbing the robber barons’ power. And he relentlessly cleaned up corruption in the federal government. One-hundred-forty-six indictments were brought against a bribery ring involving public timberlands, culminating in the conviction and imprisonment of a U.S. senator, and forty-four Postal Department employees were charged with fraud and bribery.

Now, we are in a Second Gilded Age, facing many of the same problems, and, in some ways, to an even greater degree. The gap between the rich and everyone else is even greater than it was during the late 19th Century, when the richest two percent of Americans owned more than a third of the nation’s wealth. Today, the top one percent owns almost 40 percent of the nation’s wealth, or more than the bottom 90 percent combined, according to the nonpartisan National Bureau of Economic Research. The first Gilded Age saw the rise of hyper-rich dynastic families, such as the Rockefellers, Mellons, Carnegies, and DuPonts. Today, three individuals—Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, and Warren Buffett—own more wealth than the bottom half of the country combined. And three families—the Waltons, the Kochs, and the Mars—have enjoyed a nearly 6,000 percent rise in wealth since Ronald Reagan took the oath as president, while median U.S. household wealth over the same period has declined by three percent.

The consequences of this wealth gap are dire. Steve Brill explains in his book Tailspin that, by manipulating the tax and legal systems to their benefit, America’s most educated elite, the so-called meritocracy, have built a moat that excludes the working poor, limiting their upward mobility and increasing their sense of alienation, which then gives rise to the populist streak that allowed politicians like Trump to captivate enough of the American electorate.

Similarly, psychologist Dacher Keltner’s research shows that power in and of itself is a corrupting force. As he documents in The Power Paradox, powerful people lie more, drive more aggressively, are more likely to cheat on their spouses, act abusively toward subordinates, and even take candy from children. Too often, they simply do not respect the rules.

For example, in monitoring an urban traffic intersection, Keltner found that drivers of the least expensive vehicles virtually always yielded to pedestrians, whereas drivers of luxury cars yielded only about half of the time. He cites surveys covering 27 countries that show that rich people are more likely to admit that it’s acceptable to engage in unethical behavior, such as accepting bribes or cheating on taxes.“The experience of power might be thought of as having someone open up your skull and take out that part of your brain so critical to empathy and socially appropriate behavior,” says Keltner.

That’s why we need to reform our political system if we are to survive the rampant amorality and lawlessness of the Second Gilded Age. Simply put, so very few should not wield so much sway over so many.

One of the first priorities of an incoming administration should be to narrow the wealth and income gap. French economist Thomas Picketty favors a progressive annual wealth tax of up to two percent, along with a progressive income tax as high as 80 percent on the biggest earners to reduce inequality and avoid reverting to “patrimonial capitalism” in which inherited wealth controls much of the economy and could lead essentially to oligarchy.

The leading 2020 Democratic candidates favor raising taxes, as well. Elizabeth Warren has proposed something commensurate to Picketty’s two percent wealth tax for those worth more than $50 million, and a three percent annual tax on individuals with a net worth higher than $1 billion. She has also proposed closing corporate tax loopholes. Joe Biden wants to restore the top individual income tax rate to a pre-Trump 39.6 percent and raise capital gains taxes. Bernie Sanders has proposed an estate tax on the wealth of the top 0.2 percent of Americans.

Following Theodore Roosevelt’s example, we need to aggressively root out the tangle of corruption brought on by Trump and his minions. This has already begun with multiple and expanding investigations led by House Democrats into the metastasizing malfeasance within the Trump administration. Trump’s successor, however, should work with Congress to appoint a bipartisan anti-corruption task force to oversee prosecutions and draw up reform legislation to prevent future abuses.

“Of all forms of tyranny, the least attractive and the most vulgar is the tyranny of mere wealth, the tyranny of a plutocracy,” Roosevelt once warned. The free market has made America the great success it is today. But history has shown that unconstrained capitalism and a growing wealth gap leads to an unhealthy concentration of wealth in the hands of a few. When the gap between the haves and the have-nots goes unchecked, populism takes hold, leading to the election of dangerous demagogues like Trump, and the disastrous politics they bring with them. It is not too late to reverse course. But first, we need to re-learn the lessons from our first Gilded Age if we are going to get out of the current one.